How is information shared?

Information sharing can occur in many ways, e.g., with other public sector agencies, private sector organisations, governments, groups, and/or members of the public.

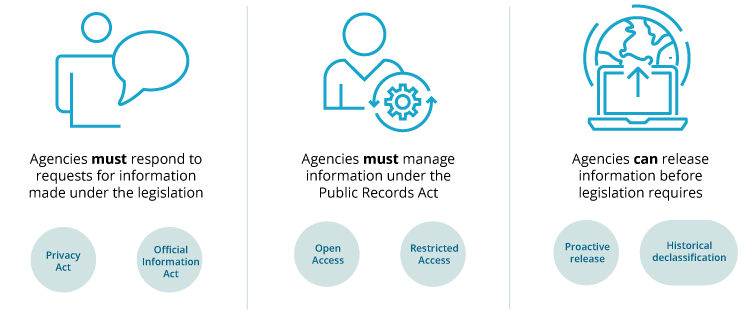

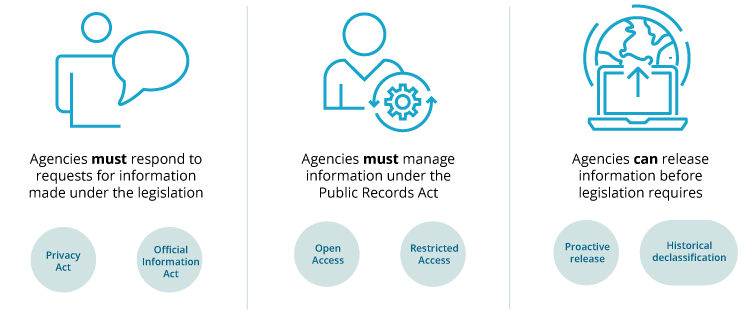

The picture below provides a simple summary of the main ways through which information is shared and the key legislation involved.

Sharing information as required by legislation

The NZ Government Classification System Policy says, “Agencies must understand their information sharing obligations under relevant legislation (e.g., Privacy Act), and regulatory or partner agreements that enable and hinder information sharing across partners.”

To achieve this, organisations need to ensure that their people understand their obligations to share information and can do so, e.g., have the appropriate training and delegations.

While it is not always obvious how valuable a single piece of information is, agencies should ensure no one feels they might be sanctioned for sharing information that they have reasonable grounds to think could prevent harm.

In general, wherever there is a threat to life or safety information can be shared. Agencies should have policies and procedures in place in the event that information needs to be shared in these circumstances.

Sharing information under the Privacy Act

The Privacy Act 2020 provides the rules in New Zealand for protecting personal information and puts responsibilities on agencies and organizations about how they must do that. The Privacy Act governs how organisations and businesses can collect, store, use and share personal information.

There are two main types of Privacy Act requests.

- Individuals, or agents acting on their behalf, can request information that is held about themselves (requests under Privacy Principle 6)

- Anyone (individuals and organisations) can request an agency or organisation to disclose personal information if they believe that the reasons for disclosure are consistent with the exceptions described in the Act.

Whenever information sharing agreements are defined in legislation, these have precedence. Where another law says you should provide information, you are always able to do so.

Information may also have additional, specific requirements about how it can be managed. For example, health information must be managed according to the Health Information Privacy Code. Further information is available from the Privacy Commissioner.

Sharing information under the Official Information Act

The OIA allows New Zealanders to have access to information that enables their participation in government and hold governments and government agencies to account.

The OIA allows New Zealand citizens, permanent residents, and anyone who is in New Zealand to request any official information held by government agencies

The principle of availability underpins the whole of the OIA. The OIA explicitly states that:

‘The question whether any official information is to be made available ... shall be determined, except where this Act otherwise expressly requires, in accordance with the purposes of this Act and the principle that the information shall be made available unless there is good reason for withholding it (emphasis added)’.

The OIA aims to increase the availability of official information (i.e., information held by a government agency) to New Zealanders. Under the Official Information Act information must be made available if requested unless a reason exists under the Act for refusing it.

While the OIA does not provide a mechanism for information sharing across Government, its principles provide a common reference point to make decisions about information sharing.

Further guidance is available from the Ombudsman.

Sharing information under the Public Records Act (PRA)

The purpose of the Public Records Act includes ‘the preservation of, and public access to, records of long-term value’.

Records may be ‘open access’ (in which case they are available to the public) or ‘restricted access’. Section 43 of the PRA requires the chief executive to categorize all public records in existence for 25 years as either open access or restricted access. Section 44 of the PRA specifies that decisions about access must be made based on whether there are good reasons to restrict public access or if other legislation which requires the records to be restricted.

When determining whether information and records should be ‘open’ or ‘restricted’, organisations should always begin with an assumption of openness unless there are good reasons to restrict. The PRA covers a range of reasons why access should be restricted including national security and international relations and preventing the disclosure of highly sensitive personal information. Without such reasons, records should be ‘open access’. Additionally, in specific circumstances, agencies may choose to allow special access to restricted records.

The PRA governs the release of archived information and is not primarily a mechanism for information sharing as described in this guidance. Further information is available from the Chief Archivist.

Other aligned legislation and policy

Agencies should understand all legislative requirements they have regarding information sharing, for example by identifying and capturing any legislation and policy that has a specific information sharing requirement. For example, the Department of Corrections lists all of its information sharing obligations on its website(external link).

General expectations of information sharing are set out in the Declaration on Open and Transparent Government(external link) through which ‘the [New Zealand] government commits to actively releasing high value public data’.

Protective Security Requirements (PSR)

The PSR is New Zealand’s best practice security policy framework. It sets out government expectations for managing personnel, physical and information security. It details mandatory information security requirements and specific protective security measures to manage the NZ Government Security Classification System and the use, handling, management, and storage of classified material. It is supported by the New Zealand Information Security Manual (NZISM) that is the technical authority for technology systems managing government information.

The PSR defines the security classification system for national security information and information received from foreign governments. NZ Government must adhere to any provisions concerning the security of such information referenced in multilateral or bilateral agreements and arrangements to which NZ or an organisation is party. Release of information requires written approval from the relevant foreign government. Further information is available from the PSR website.